My path into fantasy literature was a typical one. I started with J.R.R. Tolkien, moved on to Terry Brooks, and then jumped over to R.A. Salvatore. It wasn’t Salvatore’s legendary Drizzt Do’Urden books that captured my attention, however, but rather his under-appreciated DemonWars Saga. Where the Drizzt novels were sword & sorcery standalones, the DemonWars Saga was a sprawling, multi-volume epic fantasy that told the story of Corona. It was a familiar fantasy world full of goblins and elves, kings, rangers, and a church that held a vast horde of magic gemstones, which granted their bearers the ability to send forth bolts of lightning, fly, heal the wounded, and travel vast distances by separating their spirit from their corporeal body. The DemonWars Saga was perfect for 17-year-old me, and still holds a special place in my heart. (So much so that I’ve never reread the series, for fear of my changing tastes conflicting with my loving nostalgia.)

What set the DemonWars Saga apart from Tolkien and Brooks was its scope and willingness to let its characters philosophize and grow. The scope of Tolkien’s Middle-earth and beyond is nearly unparalleled, of course, and Brooks’ Shannara series spans generations, but Salvatore’s epic fantasy is vast in a wholly different way. It introduces readers to its protagonists, Elbryan Wyndon and Jilseponie Ault, as children and follows them through their entire lives. The challenges they face, and the themes Salvatore explores, change accordingly over time. To get to know these characters and to experience their struggles through each phase of life was unlike anything I’d ever read before. Or since.

To this day, the fourth volume in the series, Mortalis, which bridges two semi-standalone trilogies within the larger series, is one of my favourite novels. It showed a young reader how much intimacy and emotion could be packed into a fantasy novel. Salvatore wrote Mortalis in the wake of his brother’s passing—he poured raw grief into the story of Brother Francis, one of the series’ early villains, and created something magical. It showed me that epic fantasy could rely on tension and conflict that revolved around personal conflict and emotion, rather than dark lords and encroaching troll armies.

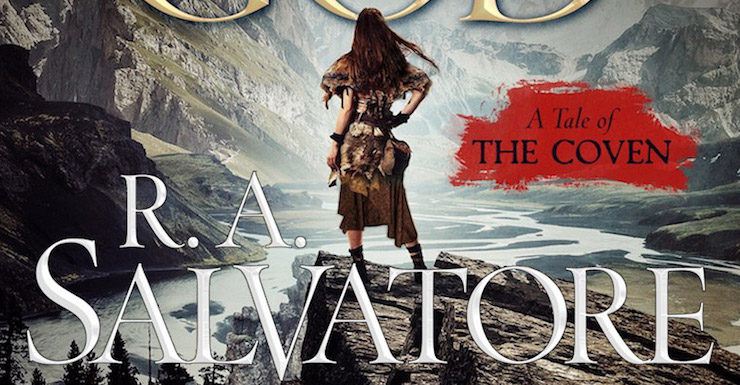

Buy the Book

Child of a Mad God: A Tale of the Coven

I say all of this, because Salvatore’s newest novel, Child of a Mad God, is a return to Corona, the first since 2010’s The Bear, and it’s impossible for me to discuss the series without also acknowledging its importance to me personally. However, it’s hardly a sequel to the DemonWars Saga. Rather than piggy-backing off the ending of the previous series, Child of a Mad God takes place concurrently with the DemonWars Saga, but is set in a wholly different region, mentioned but untouched by the original’s events, and requires no knowledge of the DemonWars Saga. (Though series fans will pick up on many cool easter eggs.) Child of a Mad God is big, fat fantasy, but, like its predecessors, the scope is tight and focuses on the long-game for a small group of characters. This melding of epic fantasy adventure with philosophical introspection is Salvatore’s bread and butter.

Child of a Mad God introduces us to Aoleyn and Talmadge, two orphans living very different lives in the northern Wilderlands. Talmadge is a trader who works with the seven tribes living in the shadow of a great mountain, Fireach Speuer. Aoleyn is a young woman living among the Usgar, preying on the seven tribes from the height of the mountain. Lurking in the shadows is the fossa, a bloodthirsty demon that hunts during the blood moon, and has a taste for magic and human flesh. Aeolyn and Talmadge’s stories unfold on parallel paths, revealing a part of Corona that is as beautiful as it is dangerous.

*Beware! Mild Spoilers.*

Talmadge is typical and comfortable, a grizzled epic fantasy hero that we’ve met before. He fled his home in the wake of a plague and now wanders the Wilderlands, fleeing the trappings of larger society. He suffers from PTSD resulting from the horrible death of his family and fellow villagers, which he tries to manage by isolating himself. Death and regret have always been a big theme in Salvatore’s novels, and Talmadge continues that trend. Where Aoleyn is always looking forward, Talmadge’s sight is constantly drawn to the shadows behind him.

A girl among the Usgar, Aoleyn is one among the women with the power to wield the Song of Usgar, which provides her tribe with its vast and dangerous magics. Despite this power, Aoleyn must navigate the complex and patriarchal politics of the Usgar. They are a mountainous people with a ferocious reputation, and regularly raid the lakeside villages beneath Fireach Speuer. Through Talmadge’s eyes, we see how effectively they use their otherworldly powers to cow the powerless villagers. The villagers fear the Usgar, do not understand them, and revere them as gods.

Child of a Mad God is very much about the convergence of cultures, and the way that socioeconomic, and religious elements affect the way that societies view each other. As an outsider, Talmadge provides the reader with a somewhat objective view of the various tribes, including the Usgar. He sees the beauty in their way of life, and holds it in some reverence, but, raised in Honce-the-Bear, which resembles pre-Renaissance Europe, he also picks apart some of their beliefs, underestimating and misunderstanding their origins.

One particular conversation stands out:

“The villagers huddle when the moon shines red.”

“Fables?”

Talmadge shook his head. “Might be, but fanciful tales believed in the heart. In all the villages. When the full moon’s red, all the tribes—even the Usgar, I am told—huddle beside great fires that steal the red glow.”

“Because there are monsters about?” Khotai asked lightly, and it was clear to Talmadge that she wasn’t taking any such threats seriously.

He wasn’t, either, when he considered just the matter of some village fables about some demonic monster, but that was only one concern.

“If we stay out through this night, our return will be met with doubting eyes,” he explained. “They’ll want to know why. They’ll want to know how. They’ll know we doubted their … fable and so do not value their wisdom. (Ch. 23)

Despite their skepticism, Talmadge and his companion Khotai recognize the social importance of respecting the traditions and beliefs of the local people.

Khotai is a mixed-race traveller with a pragmatic perspective on myth, legend, and fable, which creates its own sort of vulnerability. She’s more worldly than Talmadge, and more open in her ambitions and desire to grow, to see more of the world, and experience as much as she can. She nurtures Talmadge by pushing him to open up, to confront his demons. Through Khotai and Talmadge, Salvatore asks readers to confront their own prejudices about cultures they don’t understand.

Child of a Mad God is chock-full of women—from free-rolling Khotai, to the grizzled witch Seonagh, to young, idealistic Aeolyn—and you can tell that Salvatore has intentionally constructed his story, characters, and world in a way that is meant to be progressive and appeal to the movement towards feminist and female-friendly speculative fiction. He succeeds, mostly. Unfortunately, midway through the novel, he uses one of my least favourite tools in a writer’s repertoire: rape as a plot device. By the time it happens, we know that the Usgar are brutal and patriarchal. We know that women are treated as property by the men who form the core of the tribe’s leadership group. We know that sexual violence is a weapon, used to control the women who have access to the tribe’s magic and, thus, the power to overthrow the men. We know this. Aoleyn’s story is about growing and learning, recognizing the harsh truths of life among the Usgar, and rebelling against that. Salvatore does such a wonderful job of drawing the reader into the hostility of the Usgar, and also showcases the complex relationships between its various groups—from the men who lead, to the women who hold the power, to the slaves gathered from the lakeside villages—that I was immensely disappointed to see him fall back on rape as a way to demonize the men and victimize the women.

She was lost, and floating in empty air, leaving the world, leaving life itself. She had no idea of where Brayth had gone, or if he was still alive.

She told herself she didn’t care.

She knew it to be a lie, though, for deep inside, she did care, and she wanted Brayth to be dead.

She remembered the murderous bite of the demon fossa, and expected that her desire would be granted. Guilt accompanied that notion, but Aoleyn found that the thought of the man’s potentially horrible death did not trouble her as much as it would have earlier that evening. And so, she let it go. (Ch. 24)

Though he gives Aoleyn a quick and vicious path to vengeance, it’s still a lazy and demeaning trope that minimizes some of the other themes that Salvatore is exploring—mainly, that the “savage” Usgar are more complex than their reputation. It means that Aoleyn, who, to that point, had been portrayed as rebellious and proactive, becomes a reactive character. Her agency is stolen from her.

Salvatore’s is best known for writing the most detailed and satisfying action scenes in all of fantasy, and Child of a Mad God is no exception from this. The fights are few and far between, but when they hit, they hit hard. Violence is deeply entwined in Usgar culture, and Salvatore has immense respect for its impact both on a wider societal level, and individually. Each moment of violence, even the aforementioned use of sexual violence, has consequences.

One of my favourite aspects of Child of a Mad God is how Salvatore plays with the rules for magic he established in the DemonWars Saga. In the world of Corona, magic is imbued in gemstones which fall from the sky periodically. In the DemonWars Saga, these gemstones are collected and hoarded by the Abellican Church, and used as a tool to control the balance of political and social power. Child of a Mad God is set in a far-flung region of Corona, where the Abellican Church has little reach and no authority, but this magic still exists in a different form. Pulled from the ground and used to make weapons for the Usgar warriors, the gemstone magic warps the spread of power among the Usgar and the lakeside villages. I love the way that Salvatore explores how the magic system, which is identical at its core, is used in different ways by different cultures, with different underlying beliefs about its origin and purpose.

Though I’ve spent a fair bit of time discussing Child of a Mad God’s pseudo-predecessor, familiarity with the DemonWars Saga is not necessary. Fans will get a kick out of seeing the way Salvatore further explores the outer boundaries of the Corona, and the way the series’ trademark magical stones are utilized by less developed societies, but Aoleyn and Talmadge’s story is billed as the start of a new series and it’s exactly that. It makes reference to the previous series, but has ambitions of being something entirely new.

It’s clear that Salvatore wants Child of a Mad God to be a progressive, feminist novel, and it’s almost there, but several moments sabotage his efforts, and show how far we still have to go before we can break away from the genre’s tired tropes. That aside, Child of a Mad God is a welcome return to the world of Corona. As a big DemonWars Saga fan, I was thrilled to return, and fascinated by the way Salvatore revealed new things about the world’s magic. It can be difficult to return to a world after several years away, especially when you’re trying to craft something new, and not just a rehash of the prior stories, but Salvatore succeeds in this. It’s familiar and fresh at the same time. The DemonWars Saga is forever cemented in my reader’s soul, and Child of a Mad God reminds me of just why I fell in love with Salvatore’s novels in the first place.

Child of Mad God is available now from Tor Books.

Read an excerpt from the novel here.

Aidan Moher is the Hugo Award-winning founder of A Dribble of Ink, author of “On the Phone with Goblins” and “The Penelope Qingdom”, and a regular contributor to Tor.com and the Barnes & Noble SF&F Blog. Aidan lives on Vancouver Island with his wife and daughter, but you can most easily find him on Twitter @adribbleofink.